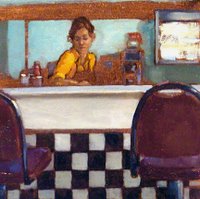

"So, hon...what'll it be today."

"What are your specials today?"

"We just got a shipment of personal responsibility in. It's really healthy (not one bit of trans-fat) and real satisfying. There are some folks here who religiously have this one. Oh yes, and it's free of charge."

"Sounds great. I'll...."

"Hold on there, sugar! There is a catch to this one."

"A catch?"

"Yeah. You have to eat all of it. If you don't eat it all, then you have to pay $100, and it's a big plate! Plus you have to keep coming back every week and get it again or we charge you another $100."

"$100??? How can you charge me for not eating it?"

"It's our restaurant. Can't we do what we want?"

"I guess so. What else is on the menu?"

"Well, one of the standard American favorites is individual freedom."

"Tell me about that."

"Well, baby, you get to eat as much or as little of it as you want, and the taste...oh, honey, it is sweet!"

"Sounds great! Ummm.... is there a catch?"

"You guessed it, darlin'. It's loaded with carcinogens, trans-fats, thimerosal, and synthetic estrogens. You will probably die young if you have this one."

"Hmmm...I guess I don't feel hungry."

There is a war going on between personal responsibility and individual freedom. This is nothing new - anyone who has raised teenagers can tell you that - but the venue it is taking is new. The raging battle has reached into the doctor's office.

A recent set of editorials in the New England Journal of Medicine discusses a plan put forth to improve the health of Medicaid recipients. The first article by Robert Steinbrook, M. D. outlines the nature of the plan:

The redesign of the West Virginia Medicaid program has recently become a leading but controversial example of efforts to reward personal responsibility. West Virginia has a population of 1.8 million; as compared with the United States, it has a higher percentage of residents with Medicaid coverage and near-poor or poor incomes (see graphs). In May 2006, the federal government approved the state's plan to provide reduced basic benefits to most healthy children and adults who are eligible for Medicaid because of low income while allowing them to qualify for enhanced benefits by signing and adhering to a "Medicaid Member Agreement." The enhanced benefits include all mandatory services as well as additional age-appropriate services that focus on wellness. Examples include diabetes care beyond basic inpatient and outpatient services, cardiac rehabilitation, tobacco-cessation programs, education in nutrition, and chemical-dependency and mental health services. Under the basic plan, prescriptions are limited to four per month; under the enhanced plan, there is no monthly limit. According to Nancy Atkins, the commissioner of the Bureau for Medical Services in the West Virginia Department of Health and Human Resources, the goals of the redesign are to streamline administration; tailor benefits to specific groups; coordinate care, especially for members with chronic conditions; and "provide members with the opportunity and incentive to maintain and improve their health."

To remain in the enhanced plan, members must keep their medical appointments, receive screenings, take their medications, and follow health improvement plans; West Virginia will monitor "successful compliance with these four responsibilities."3 Members whose benefits are to be reduced because they have not met these criteria will receive advance notice and have the right to appeal. Those who meet their health goals will receive "credits" that will be placed in a "Healthy Rewards Account" to be used for purchasing services that are not covered by the Medicaid plan. Although details about how these accounts will work and what services will be eligible for purchase are forthcoming, the services might include fitness-club memberships for adults or vouchers for healthful foods for children. In July 2006, transition to the new plan began in three West Virginia counties; the program will eventually include about 160,000 people — or about half the state's Medicaid beneficiaries. Beneficiaries who are 65 years of age or older or who have disabilities will retain their current level of coverage, as will some others, such as children in foster care. (NEJM 355:8 pg 754)

The plan seems sound: give patients motivation to change by enhancing their benefits if they do achieve certain goals that will lead to improved health. But there is a problem with this:

There are many reasons why patients might not comply with medical recommendations. These include poor physician–patient communication; side effects of medication; advice that is impractical to follow for reasons that include job responsibilities and difficulties with transportation or child care, psychiatric illness, cost, the complexity of the recommendations, or the language in which they are communicated; and cultural barriers.5 Patients who may benefit from additional services, such as diabetes care, education in nutrition, or chemical-dependency and mental health services, include many who might have difficulty with compliance, thus increasing the likelihood that they will not be eligible for these services under the West Virginia program. Moreover, as compared with elderly Medicaid beneficiaries and those with disabilities, healthy children and adults are inexpensive to cover. Any savings for these groups could be offset by the costs of administering the changes in Medicaid or by increased costs for mandatory services for patients who remain in the basic plan.

In a subsequent article, Gene Bishop, M.D. and Amy Brodkey, M.D. underline the difficulties more succinctly:

Mary Jones is your 53-year-old patient with diabetes and obesity. These conditions developed after she began to take an atypical antipsychotic drug for schizophrenia. Jones signed a treatment contract stating that she will keep all her medical appointments, attend diabetes education classes, and lose weight. She attended one class but became paranoid and left halfway through it, and she has gained 5 lb. You gave her educational materials to read, but you have discovered that she doesn't understand them. She has just missed her second consecutive appointment with you; last time, she didn't have bus fare. Neither her glycated hemoglobin nor her blood lipids are at target levels. You are now legally obligated to report this information to your state Medicaid agency, and Jones may lose her mental health benefits and some of her prescription coverage as a result. (NEJM 355:8 Pg. 756)

They go on to raise what is, to me, the crucial problems:

The plan makes explicit the belief that persons must behave according to set norms in order to deserve health care and health insurance. What physician has not sighed in frustration over the patient who continues to smoke after angioplasty? Yet while promoting healthful behaviors, we continue to offer care. The West Virginia plan risks the application of an actuarial value to every behavior. Is riding a bicycle to work good for your health because of exercise or bad for your health because of the risk of accidents? Is it irresponsible to refuse to take a medication if it makes you ill and you cannot reach your physician to ask for advice?

The plan asks physicians to violate all three fundamental principles enumerated in the Physician Charter on Medical Professionalism: the primacy of patient welfare, the principle of patient autonomy, and the principle of social justice.5 It raises potential conflicts by placing physicians in a reporting situation in which the public health is not at issue, possibly asking them to harm their patients or their relationships with patients. As physicians become agents of the state, poor patients' distrust of the medical system can only increase. Although the plan's member agreement mentions the patient's right "to decide things about my health care and the health care of my children," it does not recognize that noncompliance can be an expression of disagreement with the physician. The plan promotes discrimination not only on the basis of socioeconomic status, but also on the basis of diagnosis: surely, people with mental illnesses who have trouble managing activities of daily living such as keeping appointments will be discriminated against under a plan that rescinds their mental health benefits because of such lapses.

So here we are stuck between Scylla and Charybdis, either being sucked down by the self-indulgent waste of individual freedom or eaten by the dragon of legislated personal responsibility.

So here we are stuck between Scylla and Charybdis, either being sucked down by the self-indulgent waste of individual freedom or eaten by the dragon of legislated personal responsibility.

This is a problem basic to this country. The conflict is always between the individual freedom (championed by the libertarian) and governmental control (championed by the socialist). Clearly there are pitfalls in both, but where should we end up?

So, Sugar, what'll you have?